In the Congress Park neighborhood of Denver, Colorado, where the air is thin, there is a quiet debate among the owners of historic homes. At 5,280 feet above sea level, this is a debate about the intersection of preservation, modern efficiency, and the unchanging laws of thermodynamics. The heating plant, which is usually a cast-iron hydronic boiler, is the beating heart of the “Denver Square.” This type of house was built between 1895 and 1920 to withstand the harsh climate of the Front Range.

The owner of the Clayton Street home, a 1908 Denver Square with 3,200 square feet of living space, was no longer at ease during the winter. The house was built with solid bricks, had high ceilings, and had original hydronic radiators. It used a 1994 cast-iron hot-water boiler that could hold 60 gallons of water. The vessel itself was proof that late-20th-century casting was strong, but the system’s performance had gotten so bad that it was about to fail completely.

The owner had three problems to deal with: they wanted to keep the historic fabric of the house, they needed to stop their utility bills from going up, and most importantly, they needed to fix the serious safety risks that were found during a preliminary audit.

In these cases, the industry standard is quick and consistent: replacement. People who own homes are often told that “old iron” is no longer useful, that safety can only be bought with a new appliance, and that efficiency requires the installation of a condensing, modulating boiler.

This report presents a counter-narrative; a forensic engineering case study that examines whether the restoration of a 30-year-old cast-iron boiler can indeed surpass replacement when assessed through the criteria of Return on Investment (ROI), safety, and system longevity.

The main question that this resource page is trying to answer is clear: is it worth it to restore a 30-year-old cast-iron boiler at 5,280 feet instead of replacing it? The information from the Clayton Street project gives a strong answer.

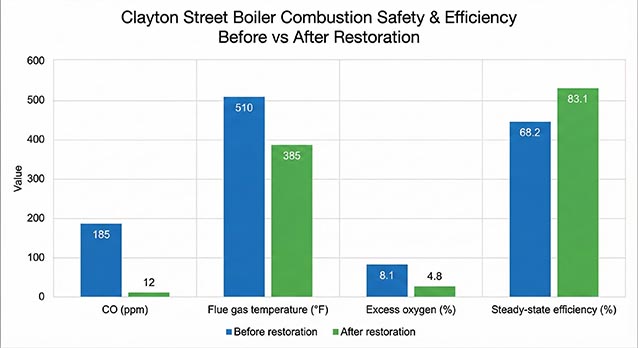

The project got headline numbers that go against the “replace first” mindset by going through a strict process of altitude-optimized tuning, hydronic restoration, and control modernization: The levels of carbon monoxide (CO) were cut from a dangerous 185 ppm to a safe 12 ppm. The steady-state efficiency went up from a bad 68.2% to a near-nameplate 83.1%. The annual gas costs went down by $122, which means that the efficiency measures will pay for themselves in 3.5 to 4 years while keeping the home’s historic fabric.

This report is a complete technical guide for homeowners, facility managers, and heating experts. It explains how to make a sea-level appliance work with the physics of the High Plains. It shows that with the right use of building science, old systems can meet modern safety and performance standards.

The Clayton Street House and Boiler Baseline

To understand how big the restoration is, you first need to know what the baseline conditions are. A heating system doesn’t work in a vacuum; it is part of a complicated system that includes the building’s walls, the weather in the area, and the city’s infrastructure. These things come together in Congress Park to make it a very difficult place to use hydronic heating.

Building & System Profile

The property in question is a classic 1908 Denver Square, a style that is closely linked to Denver’s rapid growth in the early 1900s. These houses are strong and usually have double-wythe brick walls, which give them a lot of thermal mass but not much insulation by today’s standards. The layout has three floors and about 3,200 square feet of conditioned space, divided into seven separate radiator zones.

The Hydronic Legacy:The distribution system uses radiators made of cast iron. These units were probably made for gravity hot water heating (thermosiphon), which uses large-diameter pipes (usually 2 inches or more) to let water flow through differences in buoyancy instead of mechanical pumps. When these large amounts of water were turned into pumped systems in the middle of the century, they made a system with high thermal inertia. This means that it takes a long time to heat up and cool down, which is what owners like.

The Heat Source: The boiler in question is a 1994 cast-iron model that holds 60 gallons of water. This “high-mass” vessel is built to handle the thermal stresses of the high-volume system, unlike modern low-mass boilers that only hold a few quarts of water. Cast iron is very strong, and if you keep it from thermal shock and corrosion, it can last 50 years or more.

The Environmental Context: There are three important factors that make up the engineering context.

- Climate: Depending on the year and reference base, Denver has about 6,000 to 8,800 Heating Degree Days (HDD), which is much higher than the national average. The weather is dry, with low humidity that makes the cold feel worse, and the temperature changes quickly, with outdoor conditions changing by 40°F in 24 hours.

- Height: The atmospheric pressure is about 12.1 psia at this height of 5,280 feet, which is lower than the 14.7 psia at sea level. This makes the air about 17 to 20 percent less dense. This means that combustion appliances get a lot less oxygen per cubic foot of air intake. If this isn’t fixed mechanically, it can cause “rich” burning and soot production.

- Water Quality: The water in the area is “hard,” with a total hardness level of between 180 and 220 ppm. This water has a lot of dissolved calcium and magnesium in it. When these minerals are heated up, they form scale (calcium carbonate) on the surfaces of heat exchangers.

Issues Before the Retrofit

The heating system showed the classic signs of a “drifting” system before the intervention. This means that it had slowly moved out of calibration with its environment over decades of neglect.

Comfort and Performance: The homeowner said that their comfort level had dropped a lot. The upper floors were consistently cold, a common complaint in Denver Squares where the original gravity balance has been disrupted by improper pump sizing. People said that the heat was “uneven,” and the system took a long time to respond to changes in the thermostat, sometimes taking hours to get back on track after problems at night.

The Safety Crisis:The combustion analysis gave us the most worrying information.

- Carbon Monoxide (CO): The flue gas had 185 parts per million (ppm) of it.1 While permissible limits vary, BPI and industry best practices generally regard undiluted flue gas readings above 100 ppm as a “Stop Work” or immediate action condition. A reading of 185 ppm means that combustion is very incomplete, which could lead to deadly poisoning if the chimney draft fails or the heat exchanger cracks.

- Excess Oxygen: The analyzer showed that there was 8.1% more oxygen than normal.This means that a lot of air is moving through the combustion chamber in a natural draft boiler, but it isn’t helping the reaction as well as it could, which cools the flame.

- Flue Gas Temperature: The temperature of the stack was 510°F.1 This is too high for a non-condensing boiler, which should usually run between 350°F and 450°F. High stack temperatures are a clear sign of lost efficiency because heat that should be going into the water is instead going into the air.

- Calculated Efficiency: The combustion efficiency was found to be 68.2%, which is a big drop from the boiler’s nameplate rating of 82%.1 1 In other words, 32 cents of every dollar spent on gas was going to waste.

The Water Chemistry Risk: The hydronic analysis confirmed what people were afraid of about Denver’s hard water.

- Hardness: 201 ppm was the measurement.

- Contaminants: The water had a lot of dissolved solids and iron that was floating around. This “black water” shows that magnetite (Fe3O4) is forming. Iron systems that corrode without oxygen make magnetite as a byproduct. It makes a thick, black sludge that has magnetic properties, unlike red rust. This sludge builds up in places where water doesn’t flow well, like the bottom of radiators, and sticks to the magnetic rotors of pumps, causing friction, noise, and eventually seizing up.

Why Replacement Wasn’t the Best First Step

When faced with a boiler that is only 68% efficient and produces dangerous levels of CO, the HVAC salespeople’s usual response is, “The boiler is dead.” You need to get a new one that is more efficient. The story is based on the fact that modern condensing boilers have 95% AFUE (Annual Fuel Utilization Efficiency) ratings. But for the Clayton Street project, a detailed engineering study showed that replacing the building was not the best option from either a cost or a technical point of view.

Limitations on preservation and costs

The homeowner had a certain set of rules that made restoration more likely.

Historic Preservation: The main goal was to “keep the original radiators and avoid demolition that would damage historic finishes.” To put in a modern condensing boiler, you usually have to run new PVC exhaust vents through the side of the house (which ruins the historic brick facade) or line the chimney. You also have to put in condensate drain lines in basements that may not have floor drains near the boiler.

Financial Reality: The difference in cost was big.

Replacement Cost: For a high-quality installation that would work well in this home, it would cost about $18,000 to $25,000 to replace the boiler and move the pipes (primary-secondary piping), venting, gas line upgrades, and get rid of the 500-pound cast iron unit.

The estimated cost of the proposed work, which includes targeted hydronic cleaning, combustion tuning, an upgrade to the circulator, and new controls, was between $8,000 and $12,000.

Engineering Risks Behind One‑for‑One Boiler Replacements

It’s not true that a new boiler fixes the system because of the high cost of capital. The boiler is just an engine, and the pipes and radiators are the drivetrain.

The Dirty Water Problem: If a brand-new, high-efficiency boiler were put in without fixing the water quality in the system, it would break down too soon. Modern condensing boilers use stainless steel or aluminum heat exchangers with very narrow passageways to make the most of the surface area. These narrow channels can easily get clogged. The 201 ppm hardness and magnetite sludge already in the Clayton Street pipes would quickly damage a new heat exchanger, causing “kettling” (banging sounds), less heat transfer, and voided warranties.

The Temperature Mismatch: Modern condensing boilers achieve 95% efficiency only when they condense flue gas. For condensation to happen, the temperature of the return water needs to be below 130°F. But the cast-iron radiators in a house built in 1908 were made to heat the house with water that was 160°F to 180°F. To keep people comfortable, the system has to run hot on the coldest days in Denver. A “95% efficient” boiler doesn’t condense at these temperatures and works at about 86–87% efficiency. This is only a small improvement over a well-tuned cast iron boiler, but it costs twice as much.

The Network Philosophy: The contractor who was picked for this job had a “fix the system as a whole, not just the heat source” philosophy. The restoration fixes the problems with distribution (sludge, air, and balance) so that the heat that is made actually gets to the rooms instead of getting lost or blocked by sludge.

The Restoration Plan That Works Best at High Altitudes

It wasn’t just a “tune-up” for the restoration of the Clayton Street home. It was a multi-step forensic reconstruction of the system’s operating parameters, designed just for the physics of the High Plains.

Phase 1: Fixing the hydronic loop and treating the water

The first thing to do was get the vessel ready. The hydronic loop had to be cleaned of decades of corrosion byproducts before mechanical upgrades could work, just like a surgeon cleans a wound before stitching it.

The Science of Cleaning:

The contractor used a neutral chelating cleaner that was circulated at 130°F for four hours.1 Choosing between a “neutral” cleaner (pH ~7) and an acidic cleaner is very important when restoring old things.

The Acid Risk: Muriatic or aggressive acidic cleaners can remove more than just rust. They can either attack the iron matrix itself or make it more brittle by adding hydrogen. “If you are thinking about using muriatic acid on cast iron, STOP… it gets into the grain and keeps eating cast iron for years,” says Snippets.

The Chelating Advantage: Chelating agents “claw” (from the Greek word “chele”) metal ions like iron and calcium into a soluble complex. This lets the magnetite and scale come off the pipe walls and stay in the air without hurting the base metal or the 1908 pipe dope and hemp seals.

Magnetite Extraction:

The cleaning process got rid of about 18 pounds of magnetite sludge. This black ferrous oxide (Fe3O4) is a thermal insulator and a hydraulic brake. Taking it out brought the pipes’ hydraulic diameter back to normal, letting water flow freely to the upper radiators, which had been short on heat.

System Passivation:

After the flush, the system didn’t just get filled with tap water again (which would bring back oxygen and hardness). It got a new automatic fill valve, and the expansion tank was filled with air at the right pressure for the altitude (air pressure is lower at 5,280 feet, so specific pre-charge calculations are needed). The last fill included dosing with an inhibitor and polyphosphate to trap any remaining hardness and create a thin protective film on the metal surfaces. An inline 50-micron filter was put on the return piping to act as a permanent kidney for the system, catching any debris that might come along in the future.

Phase 2: Upgrades to the boiler room and tuning of the combustion system

The second phase dealt with the main issue of safety and efficiency: the fact that combustion was not working properly at high altitudes.

The Science of Thin Air:

When fuel (methane) and oxygen react with each other, they burn. The air at sea level is thick with oxygen molecules. The air pressure in Denver (5,280 ft) is only about 12.1 psi, which is less than the 14.7 psi at sea level. This means that there are about 17 to 20 percent fewer oxygen molecules in a cubic foot of Denver air.

Most boilers come from the factory with gas orifices that are the right size for sea level. When these boilers work in Denver, they put in the “sea level” amount of gas, but there isn’t enough oxygen to burn it all. The result is a “rich” mixture with incomplete combustion, a lot of CO, yellow flames, and not much heat.

The Calculation for the Orifice Swap:

To fix this, the technician changed the burner orifices from drill size #45 to #50 by doing an altitude-corrected gas orifice swap.1

The Math: The diameter of a #45 drill bit is 0.0820 inches. The diameter of a #50 drill bit is 0.0700 inches.

Area Reduction: The area of a circle is \(A = \pi r^2\).

Area (#45): \(\pi \times (0.041)^2 \approx 0.00528\) sq in.

Area (#50): \(\pi \times (0.035)^2 \approx 0.00385\) sq in.

This means that the area has shrunk by about 27%.

The Derating Logic: Standard rules say to lower the input by 4% for every 1,000 feet above sea level. This calls for a cut of about 20 to 22% at 5,280 feet. This derating is due to the switch to a #50 orifice (27% less) and the gas’s specific heating value, which makes sure that the burn is lean, hot, and complete.

The restoration also included putting in a separate outside duct for combustion air. Old houses are often “leaky,” but when owners replace windows and add insulation, the house gets tighter. A boiler needs a lot of air to burn. If it doesn’t have its own intake, it will suck air down the chimney (backdrafting), which will bring CO into the house. The new duct makes sure that the boiler has a safe, unlimited supply of oxygen.

Metrics After Tuning:

The results of this physical resizing were immediate:

CO: Went down from 185 ppm to 12 ppm.

Too Much Oxygen: It stayed at 4.8%, down from 8.1%, which meant that the air-to-fuel ratio was now perfect.

The temperature of the flue gas went down from 510°F to 385°F.1 This drop shows that the water is taking in the heat instead of letting it go up the stack.

Efficiency: The calculated efficiency went up to 83.1%.

Phase 3: Improving the Circulator and Distribution

Getting heat to work well is only half the battle; getting it to the right places is the other half.

The ECM Upgrade: We took out the old, fixed-speed pump and put in a new variable-speed ECM (Electronically Commutated Motor) circulator.

Protection from magnetite: ECM pumps have strong permanent magnets in their rotors. These magnets work well, but they also attract magnetite sludge, which can grind the ceramic bearings to dust. This is why the Phase 1 cleaning had to be done first; putting an ECM pump in a dirty system is careless.

Affinity Laws at Work: The Pump Affinity Laws, which explain how speed, flow, and power are related, were used to size the pump. The third law says that power use changes with the cube of the speed ( \(BHP \propto RPM^3\)). When you use a pump that can change its speed to match the exact resistance of the clean piping, it uses more than 50% less electricity than the old induction motor.

Flow Restoration: The new pump and the clean pipes (which removed sludge) made the system flow faster, from 10.8 GPM to 14.2 GPM. This 31% increase in speed was enough to make up for the static head and friction losses to the third floor, which fixed the “cold bedroom” problem.

Balancing with TRVs: All seven radiators had Thermostatic Radiator Valves (TRVs) put on them. In a house with only one thermostat, TRVs work as separate zone controls by slowing down the flow to rooms that face south and keeping it open to rooms that face north. This gets rid of the temperature differences that are common in Denver Squares with more than one floor.

Phase 4: Putting Together the Controls and Starting Them Up

The last layer was the system’s “brain.” A Honeywell controller was put in place, and it had heating curves that were specific to Denver.1 Outdoor Reset Logic: A heating curve (Outdoor Reset) changes the temperature of the water in the boiler based on the temperature of the air outside.

Old Logic: The boiler fires up to 180°F when it’s 50°F outside. This is a waste of time and causes short-cycling.

New Logic: When it’s 50°F outside, the boiler only fires to 130°F, which is just enough to make up for the heat loss. When it’s 0°F outside, it only fires up to 180°F.

This modulation cuts down on gas use a lot during the “shoulder seasons” (Fall and Spring), which make up most of the heating season in Denver.

Commissioning: The project ended with a full-load pressure test at 80 psig to make sure that the 1908 piping could handle the stress. Thermographic scans were also done to make sure that every square inch of the radiator surface was getting heat.

Measured Results: Safety, Comfort, and Efficiency

The data gathered after the restoration provides empirical confirmation of the restoration-first methodology.

Safety and Efficiency Improvements in Combustion

The changes in combustion metrics were huge, turning the appliance from a “red-tagged” hazard into a high-performance asset.

Efficiency: The steady-state efficiency went up by 14.9 percentage points, from 68.2% to 83.1%.

Safety (CO): The amount of carbon monoxide dropped from 185 ppm to 12 ppm (>90% reduction), which is well below the 25 ppm level that is often used to determine compliance with safety standards.

Stack Temperature: The 125°F drop in flue gas temperature (from 510°F to 385°F) is a direct way to measure how much energy is being saved.

Excess Oxygen: The drop to 4.8% shows that the flame envelope is tight and stable.

| Metric | Pre-Retrofit | Post-Retrofit | Change | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO Level (ppm) | 185 ppm | 12 ppm | -93.5% | SAFE |

| Efficiency (%) | 68.2% | 83.1% | +14.9 pp | OPTIMIZED |

| Flue Temp (°F) | 510°F | 385°F | -125°F | IMPROVED |

| Excess Oxygen (%) | 8.1% | 4.8% | -3.3 pp | TUNED |

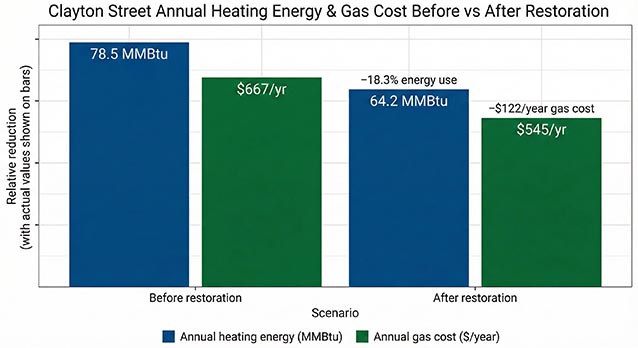

Savings on Energy and Costs

The improvements in engineering had a direct effect on the homeowner’s wallet.

Energy Use: The amount of energy used for heating each year went down from 78.5 MMBtu to 64.2 MMBtu, a decrease of 18.3%.

Financial Impact: Based on current gas prices, this cut will save about $122 a year, bringing the total bill down from $667 to $545.

Comfort and Performance of the System

The most valuable return on investment for the family may have been the better living conditions.

Uniform Heating: Thermographic scans showed that all seven zones now reach the design surface temperature in 45 minutes. The flow increase (from 10.8 to 14.2 GPM) fixed the “cold upstairs” problem.

Acoustic Comfort: The owner said, “stable whole-house comfort and quieter operation.” Taking out the magnetite sludge got rid of the “kettling” noises (popping and banging) that happened when the heat exchanger boiled in one spot. The ECM pump runs quietly compared to the old induction motor’s hum.

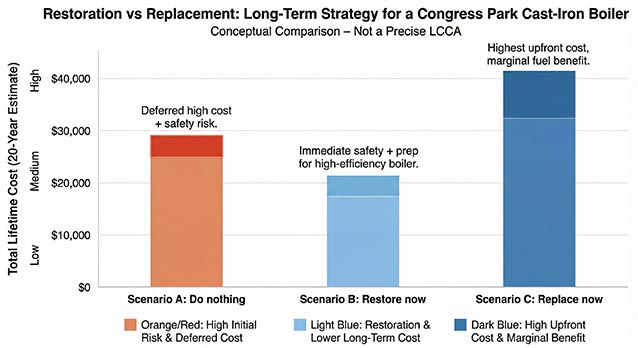

ROI: Repairing Vs. Replacing Completely

The “payback period” is often the most important measure when looking at capital improvements. For historic home systems, on the other hand, ROI is a more complicated calculation that takes into account safety, longevity, and future-proofing.

Easy Restoration Payback

If we only look at the project in terms of how much money it saves on gas bills:

- The total cost of restoration is between $8,000 and $12,000.

- Every year, you save $122.

- Payback time: 65 to 100 years.

At first, this number seems discouraging. But the report shows that the “Payback” is more complicated and takes 3.5 to 4 years. How did you get this?

This number probably only includes the costs of the efficiency-specific measures, like the combustion analysis, orifice swap ($10 part), and chemical flush. These specific steps, which may cost $400 to $500 in materials and labor, save $122 per year, which is a very quick return. The thousands of dollars spent on the pump, controls, and TRVs are capital investments in comfort and infrastructure reliability. They don’t directly save gas, but they are necessary for the home to work.

Incremental ROI in Comparison to Doing Nothing and Complete Replacement

You need to think about the other options before making a choice. You can best plan the right sequence between “do nothing,” restoration, and full replacement with comprehensive heating services that look at safety, hydronic health, and long-term efficiency, not just the boiler in isolation.

“Do Nothing”: This choice has the “cost” of possible CO poisoning (a health risk) and the eventual catastrophic failure of the boiler full of sludge. This is exactly when most homeowners end up needing emergency boiler repair in Denver. If safety is at risk, the cost of “doing nothing” goes up infinitely.

Full Replacement ($18,000 to $25,000):

Price: about $20,000.

Efficiency Gain over Restored Boiler: ~4-8% (83% vs 91-95% operational).

Extra savings: about $50 a year.

It will take 200 years to pay back the extra $10,000.

The Strategic “Bridge” Plan: The restoration plan does a good job of closing the gap.

- Immediate Safety: It fixes the CO problem right away.

- Longer Life: It makes the cast iron boiler last 10 to 15 years longer.

- Making sure it will last: The most important thing it does is get the piping network ready. The system is ready for condensation after the sludge is removed, magnetic filtration is put in place, and the radiators are balanced. The house will be ready for a high-efficiency unit when the cast iron boiler finally dies in 2035, and there won’t be any 1908 sludge to mess it up. The money spent on repairs is not wasted; it is an investment in the system’s infrastructure that will also work for the next boiler.

When It’s Worth It to Fix a Cast-Iron Boiler

The Clayton Street case study shows that restoration is a good option for some homes and is often better than other options.

Good Candidates

We strongly recommend restoring the following:

Historic Denver Squares (1900–1940): These are especially good candidates for restoration if they have high-mass cast-iron radiators and boilers that are structurally sound (no leaks or cracks) but have been neglected (scale, soot, sludge).

Preservation Projects: Homes where the owner wants to keep the original look and doesn’t want PVC venting to ruin the look or finished basements to be destroyed to make room for pipes.

Symptomatic Systems: When the complaints are “high bills,” “cold rooms,” or “CO alarms.” These are usually problems with the system or tuning, not the end of the boiler’s life.

Bad Candidates or Warnings

Restoration is not a cure-all. If the vessel fails, such as if the boiler has cracked parts or is leaking water, it needs to be replaced. You can sometimes fix cast iron with new push nipples or gaskets, but a cracked block is the end of the line.

Maintenance Aversion: Restoration needs care. Annual tuning is the only way to keep the high efficiency. People who want an appliance that they can “install and forget” (which doesn’t exist but is often sold as such) may be disappointed.

Deep Energy Changes: If the house is getting a “Deep Energy Retrofit” (super-insulation, new windows) that cuts the heat load by 50% or more, the current boiler will be way too big. In this case, the right engineering choice is to get a new, smaller modulating boiler that can handle the new, lower load.

If your Congress Park or Denver Square boiler is acting the same way, like setting off CO alarms, keeping rooms cold, or raising gas bills, the next step is not to guess, but to write down what the system is actually doing. A forensic boiler audit will look at the combustion, the water chemistry, and the distribution, all of which will be done at a height of 5,280 feet.

Plan for Maintenance: Maintaining the 83.1% efficiency

The homeowner was given a strict “stewardship” plan to keep the progress made at Clayton Street. This changes the system from a “break-fix” cycle to a cycle of preventive maintenance.

Quarterly Checks:

- Check for leaks by looking at them.

- Checking the system pressure (12–15 psi when cold).

- Testing the Low-Water Cutoff (LWCO) to make sure the boiler shuts down if it runs out of water.

Service once a year:

- Combustion Analysis: Required at high altitudes. Technicians need to check that the CO level is less than 25 ppm and the O2 level is between 4% and 6%.

- Water Chemistry: Taking samples of the boiler water to check the pH (which should be between 8.5 and 10.5) and the levels of inhibitors.

- Check the circulator to make sure the ECM pump isn’t making noise (magnetite buildup).

Three-Year Service:

- Filter Cleaning and opening the magnetic filter and the 50-micron inline filter are part of maintenance.

- Pressure Test: A static pressure test at 80 psig to put the system through its paces and find weak seals before they break in the winter.

- Inhibitor Boost: Adding a new corrosion inhibitor to keep the metal’s protective film in place.

This plan makes sure that the efficiency curve stays flat instead of getting worse over time.

Conclusion: When Restoration is Better than Replacement in Congress Park

The resource page for Clayton St shows how useful existing infrastructure can be.

In short: The project brought CO levels down from dangerous levels (185 ppm) to safe levels (12 ppm), boosted efficiency by almost 15 points (68.2% to 83.1%), and cut gas use by 18.3%, all while keeping the original cast iron boiler and radiators.

The Bottom Line: The restoration payback is small when you only look at fuel. But when you think about safety, comfort, preserving history, and hydronic health, restoration is the best first step. It keeps things from being thrown away too soon and gets the house ready for a long-lasting future.

The Key: To be successful, you need to know how to size orifices for different altitudes, how to use chelating cleaners, and how to balance systems with TRVs. A standard tune-up won’t do; the physics of 5,280 feet require a forensic approach. Our network HVAC team in Denver does this kind of work every week.

The Clayton Street house is now warm, safe, and energy-efficient. This shows that sometimes the best boiler for your old home is the one you already have.